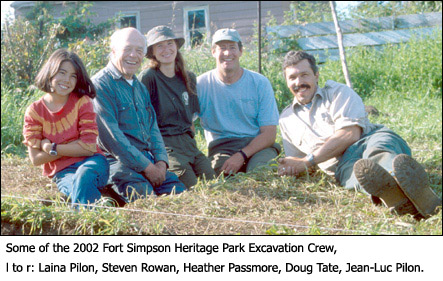

During the

summer of 2002, my daughter Laina and I were very aware that

somewhere

near

the Fort Simpson Heritage Park were the mortal remains of

François Pilon and his friends who had died of starvation in

March of 1811. We found no evidence of these burials in our

archaeological investigations during that summer, yet we were certain

they were nearby. To learn more about our research, follow

this link for the

2002 work & 2003

work. During the

summer of 2002, my daughter Laina and I were very aware that

somewhere

near

the Fort Simpson Heritage Park were the mortal remains of

François Pilon and his friends who had died of starvation in

March of 1811. We found no evidence of these burials in our

archaeological investigations during that summer, yet we were certain

they were nearby. To learn more about our research, follow

this link for the

2002 work & 2003

work.François had lived out his final days within a few dozen meters of the location where his holiness Pope John Paul II said mass in 1987 with representatives of Canada's First Nations, a truly remarkable event. Could François have ever of conceived of such a thing happening? Never.  Nor could he ever have believed that relatives of his would

one day be so close to his long forgotten and lonely tomb, praying for

him, for the rest of his soul, expressing the kinds of sentiments which

emerge at graveside during a burial, feelings that his family would

have liked to have been able to share with his neighbours and

friends. But his family probably only heard of his death years

afterwards when this news was already old news. Nor could he ever have believed that relatives of his would

one day be so close to his long forgotten and lonely tomb, praying for

him, for the rest of his soul, expressing the kinds of sentiments which

emerge at graveside during a burial, feelings that his family would

have liked to have been able to share with his neighbours and

friends. But his family probably only heard of his death years

afterwards when this news was already old news.And so, before leaving Fort Simpson, we stood quietly on the huge platform which overlooks the Papal Flats, where a pope had once stood, and we quietly prayed for our lost relative. We were certainly the first members of his family to ever ponder his fate so close to where he lay. From this platform we had a beautiful view of the mouth of the Liard River, of the promontory there still called by the French name Gros Cap, and e  ven

further up the Mackenzie River. Without being aware of it,

our gaze was directed over thousands of kilometers seeing once again

the Island of Montréal, perhaps Pierrefonds or Les

Cèdres. For a brief moment we could feel the futile hope

that François must have felt during his last days or was that

simply despair? Had he dreamed to the point of delirium of

hearing familiar voices, of smelling the wonderful aromas rising from

his mother's cooking pots, of feeling the warm breeze rising off the

waters of the mighty St. Lawrence river as it passed in front of his

ancestral home to the sounds of children playing games their ancestors

had brought over from the old country, from France generations

before? Had he

traveled one last time, in his mind at least, through that endlessly

long trip that had brought him to the Forks of the Mackenzie, perhaps

starting in front of a notary, making his mark on a contract with

MacTavish, Frobisher & Co. in 1803, spending his first winter at

Grand Portage on Lake Superior, learning all kinds of news phrases in

the Objibwa language and trading for warm moose skin clothing from his

new friends. Had he sung, for the hundredth time, those old voyageur songs created

as much to keep the rhythm of the paddle as to

preoccupy sad and suffering hearts? These were just some of the

questions and images that went through our minds. For a moment,

it was François Pilon who gave us answers. For a moment,

ever so briefly, François smiled at us, warmed by the fact that

tears had washed the earth in which he lay and that finally, his rest

could begin. ven

further up the Mackenzie River. Without being aware of it,

our gaze was directed over thousands of kilometers seeing once again

the Island of Montréal, perhaps Pierrefonds or Les

Cèdres. For a brief moment we could feel the futile hope

that François must have felt during his last days or was that

simply despair? Had he dreamed to the point of delirium of

hearing familiar voices, of smelling the wonderful aromas rising from

his mother's cooking pots, of feeling the warm breeze rising off the

waters of the mighty St. Lawrence river as it passed in front of his

ancestral home to the sounds of children playing games their ancestors

had brought over from the old country, from France generations

before? Had he

traveled one last time, in his mind at least, through that endlessly

long trip that had brought him to the Forks of the Mackenzie, perhaps

starting in front of a notary, making his mark on a contract with

MacTavish, Frobisher & Co. in 1803, spending his first winter at

Grand Portage on Lake Superior, learning all kinds of news phrases in

the Objibwa language and trading for warm moose skin clothing from his

new friends. Had he sung, for the hundredth time, those old voyageur songs created

as much to keep the rhythm of the paddle as to

preoccupy sad and suffering hearts? These were just some of the

questions and images that went through our minds. For a moment,

it was François Pilon who gave us answers. For a moment,

ever so briefly, François smiled at us, warmed by the fact that

tears had washed the earth in which he lay and that finally, his rest

could begin. |

| Back to the Introduction |

Who was this François Pilon? |