|

Léon Pilon Nile River Voyageur 1884 - 1885 |

|

|

Léon Pilon Nile River Voyageur 1884 - 1885 |

|

|

| In the early 1880s, Britain was being reluctantly drawn more and more

into the internal affairs of Egypt. A prime reason was their need to

protect, at all cost, access to the Suez Canal and the Red Sea route to India.

The stability of the Egyptian government was being threatened in the southern

part of the country over which they claimed authority, namely in the Sudan.

There, Mohammed Ahmed claimed to be a long anticipated messianic figure,

the Mahdi, and declared himself a representative or guide from God.

He preached Sudan's independence and began attacking Egyptian troops stationed

in the Sudan.

Britain eventually sent General Charles "Chinese" Gordon to oversee, as governor-general, the withdrawl of the Egyptian garrisons and the establishment of a responsible government in the Sudan. However, before Gordon's plans could be carried out, the capital Khartoum, was besieged by followers of the Mahdi. British pride required, no, demanded that all possible attempts be made to save Gordon, a British war hero. General Garnet Wolseley (yes, of Canadian Red River 1870 Rebellion fame), was put in command of the English expedition charged with saving his old friend Gordon.

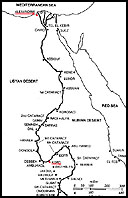

General Garnet Wolseley's plan to move an army up the Nile to Khartoum was an ambitious one that only stood a chance to succeed with the special skills possessed by the Canadian voyageurs. The Nile was a river of many great cataracts and rapids, but with the additional challenge of waters which carried heavy sediment loads and thus hid potential hazards. This proved to be one of the greatest obstacles faced by the Canadian voyageurs. "Without them, the descent of the river would have been impossible. Officers and men, they had worked with increasing energy and a complete disregard of danger."  Between their arrival in Alexandria aboard the Ocean King

on October 7, 1884, they toiled for 5 full months, guiding, lining, poling

and portaging their way up the mighty river before reaching Korti where

Wolseley established an advance headquarters. In January of

1885, it was clear that the expedition would not reach Khartoum before the

expiry of the voyageurs' 6 month contract on March 9.

They had done their duty and most were ready to return to Canada. Yet,

a surprizing 89 decided to stay on.

Between their arrival in Alexandria aboard the Ocean King

on October 7, 1884, they toiled for 5 full months, guiding, lining, poling

and portaging their way up the mighty river before reaching Korti where

Wolseley established an advance headquarters. In January of

1885, it was clear that the expedition would not reach Khartoum before the

expiry of the voyageurs' 6 month contract on March 9.

They had done their duty and most were ready to return to Canada. Yet,

a surprizing 89 decided to stay on.

"I desire to place on record, not only my own opinion, but that of every officer connected with the direction and management of the boat columns, that the services of these voyageurs had been of the greatest possible value, and further, that their conduct throughout has been excellent. They have earned for themselves a high reputation among the troops up the Nile." Adjutant General Garnet Wolseley "Si vous aviez vu nos canadiens, vous en auriez été réellement orgueilleux; les officiers en charge en sont ébahis...A l'heure où je vous écris, toutes les chaloupes qui étaient rendues à Assouan sont montées, et je suis certain qu'il y en a plusieurs qui sont déjà rendues à Dongola. Le colonel Butler, qui se trouve commandant de notre campement, disait hier que c'était extraordinaire de voir la rapidité avec laquelle marche l'expédition depuis que les canadiens sont arrivés; et nous sommes d'autant plus surpris de ce compliment que nous trouvons que l'ouvrage ne nous a pas forcés. Il nous a seulement procuré un délassement." Louis Hylas Duguay de Trois-RivièresOn January 28th, advanced units of the expeditionary force learned that Gordon had died less than two days before on January 25th. The reason for so much toil, for lost lives, had vanished. Soon, the entire rescue army would rapidly return over the course of the river which had required so much effort to climb. "...the employment of the voyageurs was a most pronounced success. Without them it is to be doubted whether the boats would have got up at all, and it may be certain that if they had, they would have been far longer in doing so, and the loss of life would have been much greater than has been the case." British officerLeon Pilon had fulfilled his contract. Great was the praised heaped upon the Canadians. All acknowledged that without them, the expedition would not have stood a chance of coming so close to their goal. Leon was one of those who decided not to renew his contract, but to return to his home. The descent of the Nile required only 9 days. At Assiout, they boarded a train to take them to Cairo. During this trip, on February 4, 1885, Leon and William O'Rourke, also of the Ottawa Contingent, fell off the train and were crushed by its wheels. The circumstances of this tragic accident were not recorded. Sources: MacLaren, Roy 1978 Canadians on the Nile, 1882-1898. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver. Stacey,

C.P. editor

|